Find out more...

Rocks mirrored in the River Meuse, between the hornbeams and the orange trees, fountains spilling into ponds and a breath of spirituality mixed with the spirit of the Enlightenment pervade the gardens of Freÿr. Enjoy their delights.

THE LOWER GARDEN: CONTEMPLATION

The canon-provost Guillaume de Beaufort-Spontin presided over the creation of the lower garden with its Baroque ‘terrace’ and its succession of ponds, the seemingly ‘embroidered’ parterres on the lawns, the interwoven lime trees, the arrangement of the orange trees around the flower beds (they previously formed a grove in front of the orangeries) and perspectives that end at the orangeries. Guillaume was a cleric and this is reflected in this part of the garden, which favours contemplation.

ORANGE TREES AND CONSERVATORIES

On October 11, 1710, the Freÿr estate’s accounts mention payment of 12 ‘sols’ to Raymond, a valet, in return for his “having carried the orange trees into the garden on the orders of Monsieur le Baron de Freÿr”. This is the first-ever mention of Freÿr’s orange trees. Some of the trees, several centuries old, are reputed to have come from the Court of Lorraine in Lunéville, although this has yet to be confirmed.

After enjoying the summer outdoors, the orange trees are returned to the orangeries, where they spend the colder months of autumn and winter. During the Second World War, the conservatories witnessed an act of heroism: Louise de Laubespin, who at the time was over 80 years old, gave up his rations of coal in order to heat the orangeries and save the orange trees,.

The orange blossoms were formerly used to produce tea and later sweets.

The Freÿr orange trees are the oldest orange trees in Europe to be grown in tubs. The consersrevatories, on the other hand, are the oldest of the former Southern Netherlands

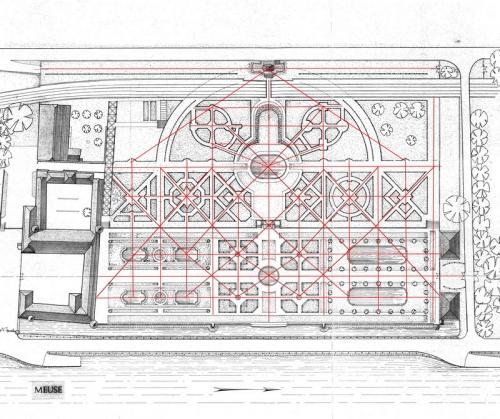

THE UPPER GARDEN: GEOMETRY

The upper garden, a small marvel of geometry, is the work of Philippe-Alexandre, a freemason and admirer of the Enlightenment. Between the hornbeam mazes, three axes perpendicular to the Meuse can be seen. A junction was created between the parterre and the new upper garden, crowned in 1775 by an elegant Rococo pavilion. This part is more in the spirit of Louis XV.

FRÉDÉRIC SAAL

The pavilion bears the name Frédéric Saal in homage to the heir of the estate, Frédéric-Auguste-Alexandre (Saal means ‘room’ or ‘space’ in German). In addition to the work of local craftsmen, this little jewel - which Victor Hugo, who was visiting, found little to his taste (describing it as “mannered patisserie”) - is the work of the Moretti stucco artists, as witnessed by a medallion representing drunken putti and inscribed ‘Moretti fecit’ (Moretti made this) in the central part of the pavilion.

From the Saal pavilion, there is a majestic view towards the river. To imagine and create this axis, which opens onto the Meuse and ends with Frédéric Saal pavilion, Philippe-Alexandre called upon the Parisian architect P J Galimard.

TWO-FACED BUSTS

According to some authors, these two-faced busts are the ‘soul of the gardens’. They are attributed to the Lorraine sculptor Paul-Louis Clyffé (1724-1805), who was a modeller, carver and artist for King Stanislas 1st Leszcynski, Duke of Lorraine, for whom he decorated palaces and gardens.

The two-faced busts of Freÿr are the only known example of this type of statuary in Belgium: they are in terracotta and made in neoclassical style, using moulds. They represent Roman emperors and emperors of the Germanic Holy Roman Empire, as well as horsemen and elegant ladies.

In order to prevent theft, the original busts have been removed and today it is these replicas in artificial stone that look out towards the Meuse and gaze at the hornbeams.

THE SMALL MAZES

The eight masses of hornbeam hedges in the upper garden, on both sides of a vertical axe and looking out from the pavilion towards the Meuse, are intricacies that compose a maze, where one can lose oneself or find peace and quiet.

THE DOME AND BOWER OF LIME TREES

At the top of a small set of steps, by the farm and the barn, the shady path that you walk from the parterre to the upper garden is covered by lime trees, pruned in a fan shape to form a vault that crowns the hornbeam bower. Midway along the path is a dome, also patiently created by taming the upper branches and boughs: a work of true gardening artistry.

THE HYDRAULIC SYSTEM

The water in the gardens of Freÿr comes from the spring La Rochette, in the Grotte des Moines (the Monks’ Cave). The rising water has in fact already flowed some 1,500 metres from the nearby hills. From the cave it travels a further kilometre via a subterranean aqueduct, over an accurately calculated slope, and makes its way, with occasional diversions, to the settling chambers. From there, the water continues on its way to feed the ten ponds and fountains, through to the garden on the south side of the château, before flowing into the River Meuse.

BEYOND THE WALLS

At Freÿr, the environment – the Meuse, the cliffs, caves and woods – form a ‘sublime’ (according to one of the concepts used by the 18th century philosophers), even ‘picturesque’ screen for the delicately-designed gardens. Paradoxically, it is this sharp contrast that forms the ensemble that is Freÿr, encompassing the two banks of the river and connecting the Meuse to the gardens.

It is from the Frederic Saal pavilion that one has the most beautiful view over the surrounding nature: tamed and serene towards the north where, passing over the flower beds, our eyes finally come to rest on the mirror of the Meuse; towards the south on the other hand, there is a more powerful spectre, where the view collides with the cliffs that rise up opposite the château.

Discovering the estate of Freÿr, and particularly its gardens, is especially striking when seen from the top of the cliffs on the right bank of the Meuse. On the extreme left of the gardens, the château seems more like a detail. The hornbeams, which are mysterious and convoluted as you walk through them, appear from this distance in all the glory of their 6 kilometres of hedges, composing a range of perfectly symmetrical paths and rooms.

The transition between the majesty of the gardens and the stretches of forest and rocks is also startling. The spectacle appears to be timeless. Indeed, it is true that, with the exception of the road linking Dinant and Givet, the view has not changed since the 18th century.

Two drives, the Allée Gilda (in the south, towards Givet) and the Allée John (in the north, towards Dinant) prolong the perspectives and, for those arriving at the estate, announce the majesty of the Freÿr.

Above the Frédéric Saal pavilion, a meadow-orchard has been created, restoring the land to its former landscape. The trees are typical of the Mosan valley. A rare species of bat, as well as a local breed of sheep and all sorts of birds and insects once more co-exist in this favourable habitat.